by Bob Benenson, FamilyFarmed

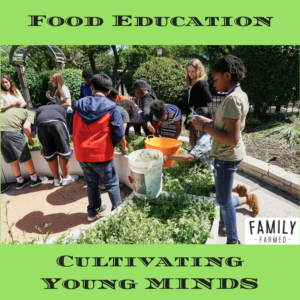

The first thing you notice if you visit a school with a Learning Garden from The Kitchen Community non-profit organization is … joy. The chance to get their instruction outdoors instead of in the classroom — learning to put seeds in soil, nurture the plants, and then harvest the food they have grown — is something the children really seem to relish.

Students are taught to use the math, science and other subjects they are studying as they tend to the garden. Yet it may take a few years, at least for the little ones, to realize what serious purposes are behind this fun school time.

Students are taught to use the math, science and other subjects they are studying as they tend to the garden. Yet it may take a few years, at least for the little ones, to realize what serious purposes are behind this fun school time.

The Kitchen Community aims for these Learning Gardens to help instill healthy eating habits at a very young age, so the kids — many of them living in communities with low access to nutritious food options — will grow up understanding what “Real Food” is and demand it.

Learning Gardens also are intended to build an atmosphere of cooperation, teamwork and mentorship within the schools, and to create a better connection between the schools and their surrounding communities. And for children growing up in urban environments that are almost entirely man-made, the gardens provide an important glimpse into the grandeur of nature.

The Kitchen Community is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization co-founded by visionary social entrepreneur Kimbal Musk. In just a few short years, the nonprofit has built nearly 400 gardens nationwide. That includes 144 in Chicago alone, a number that is planned to increase by 10 more this fall.

And a $2 million grant from Wells Fargo Bank, announced during a garden planting ceremony at Wendell Smith Elementary School on Chicago’s far South Side on May 30, will enable a quantum leap forward. According to Sam Koentopp, Program Manager for The Kitchen Community in Chicago, the group’s goal is to be in 10 regions with 1,000 gardens by 2020.

The Kitchen Community’s Learning Garden initiative aims to have a great impact on students located in low-access communities. “During our application process we look at low-income numbers and free and reduced lunch numbers, and try to target schools that have the greatest need. In food desert communities where there is less green space, the built environment isn’t supporting nature spaces,” Sam said. “We try to augment those schools with more opportunities.”

Mike Biver, The Kitchen Community Development Manager, agreed, saying, “It would be fair to say we focus on underserved communities,” though he added, “We won’t necessarily limit it to low-access communities. We put a higher priority there, but you’ll find us in other communities as well.”

This mix was evidenced in the three schools FamilyFarmed visited with The Kitchen Community this spring. Two of them were located in economically challenged neighborhoods on the South Side: Wendell Smith in North Pullman and Ruggles in Chatham. The other, Walt Disney Magnet Elementary School, is in Buena Park on the more affluent North Side, very close to Lake Michigan, though like the other two schools, the student body is mostly minority.

The most obvious priority is to shape how the children think about food — not surprising for a program that mainly teaches kids to grow plants that they can eat.

Sam Koentopp, Chicago Program Manager for The Kitchen Community, instructed children at Chicago’s Wendell Smith Elementary School in seed planting during a May 30 garden installation. Photo: Bob Benenson/FamilyFarmed

“We are really striving to create a generation that values food, values food that they trust and that they themselves have a healthy relationship with,” Sam said. “You may have a relationship with a box of Oreo cookies. That’s a very different relationship you have with the produce that you have spent your childhood growing and eating and feeling a deep connection with and knowing how it makes your body feels, and being taught and learning and seeing the impact that food has on our environment. It doesn’t take a lot to see and make those connections. Young people, adults, we know what Good Food is. When we eat it, we know.”

He added, “We all know that packaged, heavily processed foods… are delicious, they taste really good. Salt and fat and sugar are spectacular things to put in our mouths. But there’s a price for that. We as humans need to learn that there’s a better way for us to eat, that can include those things, just it also has to include more of the things that are grown in the ground and delivered straight to us.”

According to Mike, “Kids are literally hungry for this information. They are drawn to it.”

He shared an anecdote from the program: “I was talking to a volunteer who came out to a planting day, and the Learning Garden, as is often the case, was right next to the playground. She was sitting waiting for the students to come out and she was anticipating complete chaos [thinking] these kids are going to come out and they’re going to be on the playground the whole time, we’ll be constantly wrangling them back to the garden. She said as soon as the kids came out, they immediately went to the Learning Garden, without any instruction, and started playing with the soil, looking to see what was going on. They want to know.”

FamilyFarmed staffers on June 9 volunteered at Harvest Day at the Walt Disney Magnet Elementary School, one of The Kitchen Community’s garden sites on Chicago’s North Side. In the top photo (from left), FamilyFarmed’s Leah Lawson, Katie Daniel and Chelsea Callahan chat with students; on the bottom, FamilyFarmed CEO Jim Slama discusses the program with Mike Biver, The Kitchen Community’s development manager. Photo: Bob Benenson/FamilyFarmed

Environmental sustainability is another pillar of the Real Food movement. “We’re not just looking at this built environment, we’re looking for insects in the soil, talking about the microbes, about the life in the soil, experiencing nature at a very close, deep level. And a long-term vision, that is a very impactful experience for those students. Their eyes are opened, and as they grow, as they learn, as they have more experiences, they’ll be able to see and find nature in more places…,” Sam said. “Hopefully, just as we instill an appreciation and a value for Good Food, we also instill a value for the natural world. You can’t remove those two things from each other. They are intrinsically connected.”

Building a greater sense of community — both within and outside the schools — also is a first-tier issue for The Kitchen Community. One thing that jumped out during a visit to the Ruggles school on May 17 was how the older children, brought out first to start the planting, instantly became assistant instructors teaching the younger students that followed them into the garden.

Students at Ruggles Elementary School on Chicago’s South Side received a lesson from The Kitchen Community staff on how to install drip irrigation lines in the school’s new garden boxes on May 17. Photo: Bob Benenson/FamilyFarmed

Sam also related a story about how students and teachers at the Mary E. Courtenay Language Arts Center school in Uptown on the North Side collaborated to design and build kneeling platforms so students with physical disabilities could fully participate in the school’s garden.

Said Sam, “Teachers and students are finding new ways of engaging together, supporting students in their school who need extra support, students with physical disabilities, and social, emotional challenges. It’s about teachers, parents, students and community members all working together in their garden. All these things that ripple out from the garden. It doesn’t happen at every school, but it happens frequently enough that it really shows that you just need some sparks…. It’s really a powerful healing space.”

FamilyFarmed plans to follow The Kitchen Community’s Learning Gardens through the seasons — including this summer, when we will visit gardens maintained by their local communities while the schools are out of session.

The Kitchen Community received a ceremonial check representing a $2 million donation from Wells Fargo Bank, in a ceremony held at the end of a garden installation at Wendell Smith Elementary School on Chicago’s Far South Side on May 30. Photo: Bob Benenson/FamilyFarmed