By Bob Benenson and Jim Slama, FamilyFarmed

Chicago on Monday hosted the annual James Beard Foundation culinary awards ceremony for the first time, and Rick Bayless — one of the city’s most decorated and highest profile chefs — was frequently on the stage as one of the event’s co-chairmen.

Celebrated Chicago Chef Rick Bayless spoke about his commitment to local farms at FamilyFarmed’s Good Food Festival & Conference on March 19. Photo by Bob Benenson.

Famed for popularizing regional Mexican cuisine in the city at his Frontera Grill and Topolobampo restaurants, Bayless won his first James Beard award — Best Chef Midwest — at the organization’s inaugural ceremony in 1991, and his most recent this year for Best Podcast (The Feed, which he co-hosts with Chicago food critic Steve Dolinsky). In between, he received James Beard medallions as National Chef of the Year in 1995 and Humanitarian of the Year in 1998, and Frontera Grill received the organization’s Outstanding Restaurant award in 2007.

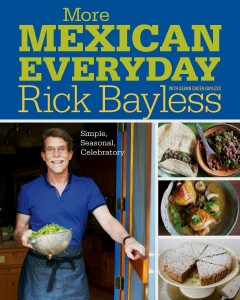

He has a long-running public television show (Mexico: One Plate at a Time), won the Bravo network’s Top Chef Masters competition in 2009, and has written several cookbooks, including More Mexican Everyday, which was just released on April 27.

Yet it is Bayless’ role as a pioneer in helping establish a market for local, sustainably produced — and delicious — food in the Chicago region that, to advocates of the Good Food movement, is one of his greatest lifetime achievements.

It is not just that Bayless has provided small farmers with income by purchasing the products that they grow or raise. In order to ensure that these farmers could produce a sufficient supply of ingredients for his popular restaurants, Bayless has provided dozens of farmers with financial support to scale up their operations through the nonprofit Frontera Farmer Foundation, which provides grants to farmers to purchase equipment.

“It’s huge and he’s done this with farm after farm after farm,” said Marty Travis, who runs The Spence Farm in Fairbury, Illinois with his wife and son.

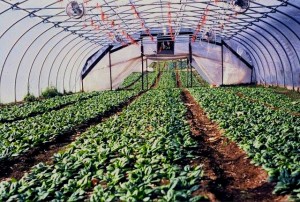

The Spence Farm in Fairbury, Illinois, located and produces a nearly extinct variety of Iroquois corn that was sought by chef Rick Bayless.

Travis cemented a relationship with the Frontera restaurant group by tracking down a rare and almost extinct heirloom variety of Iroquois corn that Bayless sought. The Spence Farm, which also provides Bayless with specialty products such as squash blossoms, received a grant from the Frontera Farmer Foundation in 2008 for a mill to process the roasted Iroquois corn into meal.

In turn, his work with Frontera raised the profile of Spence Farm to the extent that it has become an important supplier to other top Chicago chefs, such as Stephanie Izard, Chris Pandel, Paul Kahan, and Jared Van Camp.

Greg Gunthorp, a fourth-generation farmer of pastured-raised hogs in northeast Indiana, became the leading poultry and pork provider for the Frontera group’s restaurants. “Rick is really, really serious about local sustainable agriculture,” Gunthorp said. “You couldn’t ask for a better customer.”

Gunthorp had to greatly expand his livestock operation to fully develop his partnership with Frontera, ultimately becoming one of the few relatively small, sustainable meat producers to build and operate a USDA-inspected on-farm processing plant. He also benefitted from Frontera’s generosity. Gunthorp, utilizing the short-term lending program Frontera operated prior to the Foundation, borrowed the same $10,000 — repaid and then re-borrowed — several times as he scaled up his business.

“We used that program quite extensively,” Gunthorp said. “There were a few times I’m sure that we’d have really, really struggled, and maybe we wouldn’t have been able to continue, if it wasn’t for the financial assistance from the restaurant, because access to capital was a huge, huge issue during our growing phase.”

All About the Flavor

When Bayless made it his personal mission to help build a functioning local food system in the Chicago region about a quarter-century ago, he was driven by a culinary goal. He simply wanted to provide his customers with the most delicious food possible.

Bayless developed a fascination with Mexico while growing up in an Oklahoma City restaurant family that specialized in barbecue, and before moving to his wife Deann’s hometown of Chicago, he had spent five years living south of the border and deeply researching the nuances of the nation’s regional food cultures.

“What I had learned in Mexico is that all of the great pockets of wonderful regional food all had the best local agriculture,” Bayless recalled during a March 19 panel discussion about Frontera Foods at FamilyFarmed’s Good Food Financing & Innovation Conference. (Watch a video of this panel discussion by clicking here.) But at the time, there was a severe scarcity of locally produced ingredients, as most of the region’s bountiful farmland had long since been given over to commodity crops such as feed corn and soybeans.

A panel on Rick Bayless’ Frontera food enterprises on March 19 included (from left) FamilyFarmed President Jim Slama; Bayless; livestock farmer Greg Gunthorp; Manny Valdes, CEO of Frontera Foods; and Tony Owen of DOM Capital Group, a financial partner in Frontera’s recent expansions. Photo by Bob Benenson.

If Bayless had not been as committed to replicating the freshness and vitality of the food he experienced in Mexico, it would have been easy enough for him to cut corners. His talent and the novelty of the dishes he was serving — at a time when most Americans, in Bayless’ words, thought Mexican food was “all one color, all one texture and covered in melted cheese” — made Frontera a big hit after its opening in 1987 on Chicago’s Clark Street, and he soon created Topolobampo as a fine dining concept right next door.

But Bayless and the talented kitchen team he built recognized that their preparations were not all they could be. “It was clear that those pink tomatoes from the commodity market were compromising the quality of food,” said Tracey Vowell, who spent a long tenure as executive chef for Frontera Grill and Topolobampo before she went into farming herself about a decade ago at Three Sisters Garden in Kankakee, Illinois. “You could see it, you didn’t even have to put it in your mouth. It didn’t have the right color, it didn’t have the right texture in the pan.”

The Frontera team scoured the few farmers markets that existed in Chicago at the time with such thoroughness that they were viewed almost like an invading army. “We were buying a substantial percentage of the total stuff that they brought to market. They weren’t particularly happy to see us coming,” Vowell said.

Green for Greens

But Vowell was also charged by Bayless with developing direct supplier relationships with area farmers. One of these was Snug Haven Farm in Belleville, Wisconsin (near Madison), which impressed Bayless with its sweet-tasting, hoop house grown winter spinach, and also became a major supplier of tomatoes, picked ripe and frozen whole, that became a staple of his kitchen during the off-season.

The extraordinarily sweet winter spinach grown in hoop houses by Wisconsin’s Snug Haven Farm prompted chef Rick Bayless’ first act of financial assistance that ultimately led to the Frontera Farmer Foundation.

Winter spinach, like many cold-weather crops, has a heightened level of sweetness. As Bill Warner, who owns Snug Haven with his wife Judy Hageman, describes it, the starches in the plants convert to sugar, which acts as an anti-freeze. “People who have been buying it all year at our winter market taste it and go, ‘This is the best ever.’ It’s truly phenomenal in January and February,” he said. Bayless, describing his first sample of the product two decades ago, said it was “the sweetest spinach I’d ever tasted.”

It was out of this relationship that Frontera’s direct financial assistance to farmers was born about 20 years ago. Warner and Hageman had committed to building a second hoop house at Snug Haven to supply Frontera’s growing need for its spinach, when the family ran into unexpectedly expenses that put the project at risk.

“I’d always see Tracey, and I said, ‘We’ve got these tomatoes [as collateral], could we borrow a bit?’” Warner recalled. “She talked with Rick, and we had a couple more expenses, and she said, ‘If I don’t put a ceiling on it, how much do you really need?’ I said, ‘What about $10,000.’” Frontera loaned that amount, which Snug Haven used to complete the hoop house and paid back well in advance of the one-year deadline, Warner said.

Frontera also went the extra mile to provide its vendors with upfront cash when needed. Warner said the restaurants at times paid in advance for the Snug Haven tomatoes that were frozen for delivery during the off-season. Gunthorp — who is committed to only selling chickens that have spent their whole lives eating outdoors — received advance payments for poultry that he processed and froze for delivery during the winter.

“Thanks to chefs like Rick Bayless, we truly are an American Dream success story,” Gunthrop said. “It’s taken us beyond my wildest dreams.”

Tracey Vowell worked for Rick Bayless for many years as the Frontera restaurants’ executive chef, then became a farmer and supplier herself about a decade ago.

Vowell, who went from obtaining food from local farmers to becoming a farmer herself, said Frontera’s loyalty to its suppliers provides them with perhaps the most crucial element in making a go of it financially: predictability of income.

“When we starting farming, the first thing we did right out of the box is say, ‘We have to build a greenhouse and produce something all year round,’” Vowell said. “I’m a cook, I don’t know about this living off nine months of income for 12 months. I’m going to die somewhere in December and January. So we built the greenhouse and starting growing pea shoots. They signed on with us at the very beginning with standing orders. We had that level of expectation.”

She continued, “The second year we started growing black beans. And boom, we have this big order that goes to Frontera almost every week. Because we have that basis, we know the mortgage is paid, whatever, so you can move over and take risk that you might not have been necessarily able to if you did not have that basis in the bank.”

Travis at The Spence Farm said the Frontera operation can be almost too generous to its farmers. He recalled that when he brought his first batch of Iroquois corn meal to Chicago, Brian Enyart, then the chef de cuisine for Frontera and Topolobampo, “set it on the counter and almost cried.” When Enyart said he’d pay $20 a pound for it, “We said, ‘Brian, that’s too much, we couldn’t possibly go back and live in our community selling corn at $20 a pound.’ We had farmers who were selling it for $3 a bushel.” Travis said they ultimately settled on $15 a pound.

The Spence Farm in turn has become a benefactor for small farmers who are seeking to cultivate the Chicago market as it has. Travis and his family first created Stewards of the Land, a coalition of sustainable farmers within a 50-mile radius of their hometown of Fairbury, and 10 years ago launched the Spence Farm Foundation to provide educational opportunities for farmers who want to pursue this type of growing and chefs who work with local farmers.

Grants to Grow

Bayless’ loan program continued for several years before evolving into the Frontera Farmer Foundation, which makes outright grants. Here is how Bayless explains its operation:

“The Frontera Farmer Foundation will award grants for capital improvements of up to $12,000 to small and medium-size, individually owned farms that sell their food products to customers in the Chicago area at farmers markets and otherwise. Farmers must have been in business for at least three years and must demonstrate how the grant will improve both their farm’s viability and the availability of locally grown food products in the Chicago area.

“Grant applicants will be judged on the basis of demonstrated need, long-term dedication to sustainable farming, creative and business acumen, and commitment to sustainability. Applicants will also be judged on their past history with the foundation. Additional grants will be approved only after a farm has demonstrated the initial grant had a measurable impact on the farms infrastructure and ability to provide locally grown food to the Chicago area.

The foundation has awarded roughly $1.5 million since its inception and has awarded grants to more than 60 farms in Illinois, Wisconsin, Indiana and the Michigan. Many have received more than one grant over the years.”

The grants address a wide range of needs. Travis received funding for his corn mill. Others that have been funded include Shooting Star of Mineral Point, Wisconsin, which received a $10,675 grant in 2004 for hoop houses and winterization of its packing shed, and Blue Skies Berry Farm of Brooklyn, Wisconsin, which received a 2005 grant of $7,900 for a cold frame, tractor bearings, and a washing shed.

Garden in the City

Bayless has set his own example to encourage expansion of the rising urban agriculture sector in Chicago, whose motto is Urbs in Horto (Latin for “City in a Garden”). His extensive landscaped garden in the city’s Bucktown neighborhood and the rooftop growing operation atop his Clark Street restaurants — managed by horticulturist Bill Shores — provide food that ends up on his customers’ plates.

The success of these plots has made Bayless bullish about the future of urban growing. “When you can grow $30,000 worth of produce in our backyard, if you can do that, it says urban agriculture is viable,” Bayless said. “Every farmer in this climate is now learning to grow year-round. They’re going back to the old ways of farming, but adding new technology. When you see how much more stuff we have year-round from farmers versus 10 years ago, it’s a drastic increase.”

More Mexican Everyday, the latest of a series of cookbooks by chef Rick Bayless, reflects the increased availability to U.S. consumers of fresh, authentic Mexican ingredients.

In fact, the entire landscape of local food has expanded so dramatically that Bayless said it inspired him to write his new cookbook, a sequel to his very popular Everyday Mexican from a decade ago. “In the 10 years between the books, there’s been an explosion of farmers markets and supermarkets have made better produce more widely available,” Bayless said. “I want to answer the question, ‘What the heck do we do with all of this stuff?’”

Bayless now presides over an expansive — and expanding — enterprise that, along with Frontera Grill and Topolobampo, includes Chicago’s two Xoco restaurants that feature his take on Mexican street food, one immediately adjacent on Clark Street and the other in the hip community of Wicker Park; and packaged items such as restaurant-style chips and salsa that sell under the Frontera Foods brand, run by Manny Valdes, his longtime business partner.

Valdes, who appeared on the panel with Bayless at the Good Food Financing & Innovation Conference, said, “We’ve had the amazing luxury of really developing a product line that is closely associated with the restaurant. There have been other chefs who have launched products that are associated with the restaurant only in name. It may have the restaurant’s name or it may have the chef’s signature, but that’s about as for as it goes, it’s just a marketing play. Our products are so closely aligned with what we do in the restaurant, that’s our research and development.”

But the development that of late has caused the most buzz about Bayless is Tortas Frontera, a fast casual meets fine dining concept in, of all places, a concourse at Chicago’s vast O’Hare Airport.

Tony Owen of Chicago’s DOM Capital Group, which has become a financing partner with the Frontera group in its expansions, said at the Good Food Financing event that the aim is to “be successful at exposing a larger group of people to the authentic flavors of Rick’s cuisine.” But he said Bayless and his team are proceeding as deliberately as they did on Frontera’s packaged foods.

“The goal is to do that in a very considered way, not to expand too quickly, and also to be careful about selecting the right sites,” Owen said.

And they are having fun doing it.

In a comic video for this week’s James Beard Awards (produced by Chicago’s The Second City, BOKA restaurant group co-owner Kevin Boehm, the Choose Chicago tourism organization, and the Illinois Restaurant Association), Bayless said he was up for a prize for “fine dining between Gates H2 and H19.”

He also joked during his talk at the Good Food Financing & Innovation Conference, “I think there will be an epitaph on my tombstone that says, ‘He made good food in an airport.’ I think that’s what I will be most known for.”